Python Machine Learning Tutorial: Predicting Airbnb Prices

Machine learning is pretty undeniably the hottest topic in data science right now. It's also the basic concept that underpins some of the most exciting areas in technology, like self-driving cars and predictive analytics. Searches for Machine Learning on Google hit an all-time-high in April of 2019, and they interest hasn't declined much since.But actually learning machine learning can be difficult. You either use pre-built packages that act like 'black boxes,' where you pass in data and magic comes out the other end, or you have to deal with high level math and linear algebra. Either approach makes learning machine learning challenging and intimidating.

This tutorial is designed to introduce you to the fundamental concepts of machine learning. As you follow along, you'll build your very first model from scratch to make predictions, while understanding exactly how your model works.

(This tutorial is based on our Machine Learning Fundamentals course, which is part of our Data Science Learning Path. The course goes into a lot more detail, and allows you to follow along writing code interactively so you can learn by doing. If you're seriously interested in mastering Machine Learning, we recommend you take that course and the other machine learning courses in our Data Scientist path.)

What is Machine Learning?

In a nutshell, machine learning is the practice of building systems, known as models, that can be trained using data to find patterns which can then be used to make predictions on new data.

Unlike a lot of other programming, a machine learning model is not a rules-based system where a series of 'if/then' statements are used to determine outcomes (e.g. 'If a student misses more than 50

Instead, machine learning model examines the statistical relationships between data points in a data set with defined outcomes, and then applies what it has learned about those relationships to analyze and predict outcomes for a new data set.

How Machine Learning Works

To better understand the basics of machine learning, let's look at an example. Imagine we're selling a house and we want to determine an appropriate listing price. What we might do — and what realtors actually do — is look at comparable houses in our area that have already sold. In machine learning terms, each house we look at is known as an observation.

For each house, we'll want to consider factors such as the size of the house, how many bedrooms and bathrooms it has, how far it is from amenities like grocery stores, etc. In machine learning terms, each of these attributes are called features.

Once we've found a number of similar houses, we could then look at the prices they've sold for, average those prices, and come to a pretty reasonable prediction about the value of our own house.

Looking at similar houses can help you decide on a price for your own house.

In this example, the 'model' we built was trained on data from other houses in our area — observations — and then used to make a prediction about the value of our house. The value we are predicting, the price, is known as the target variable.

Of course, this example isn't truly "machine learning" because we handpicked the "observation" houses to study based on the features of our own house. Trying to do this sort of thing on a larger scale — like predicting the price of _any_ home in a city based on a large real estate data set — would be incredibly difficult for a human. The more observations and features there are, the more difficult such an analysis becomes to do by hand, and the easier it is to miss significant-but-not-obvious patterns in the data.

That's where machine learning comes in A real machine learning model could do something quite similar to our little house prediction model on a much larger scale by:

- Examining a large data set of past home sales (observations)

- Finding patterns and statistical relationships between a house's characteristics (features) and its price (the target variable), including patterns that might not be evident to a human who's looking at the data

- Using these statistical relationships and patterns to predict the price of any new houses we feed it data on.

The model we're going to build in this tutorial is similar what we've outlined above. We're going to be make Airbnb apartment rental price recommendations by building a simple model using Python.

(This post presumes you are familiar with Python's pandas library — if you need to brush up on pandas, we recommend our two-part pandas tutorial blog posts or our interactive Python and Pandas course.)

Predicting Airbnb Rental Prices

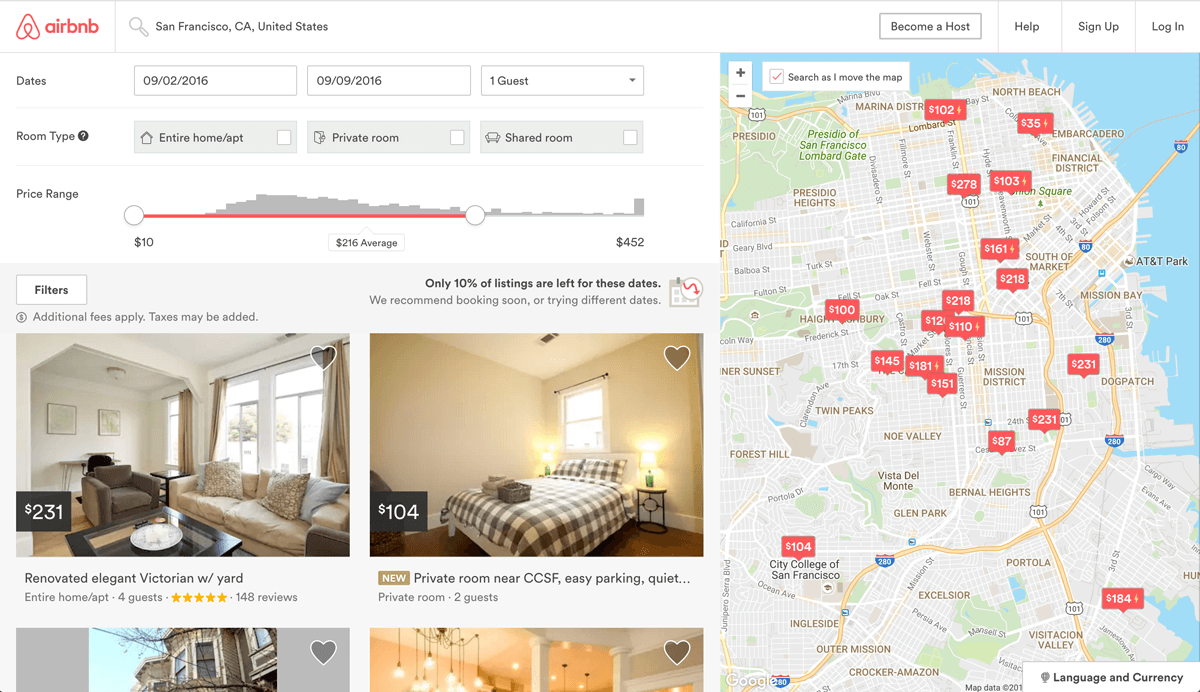

For the uninitiated, Airbnb is a internet marketplace for short-term home and apartment rentals. It allows you to, for example, rent out your home for a week while you're away, or rent out your spare bedroom to travelers. The company itself has grown rapidly from its founding in 2008 to a valuation near US$40 billion and is currently worth more than any hotel chain in the world.

One challenge that Airbnb hosts face is determining the optimal nightly rent price. In many areas, would-be renters are presented with a good selection of listings and can filter by criteria like price, number of bedrooms, room type, and more. Since Airbnb is a marketplace, the amount a host can charge on a nightly basis is closely linked to the dynamics of the marketplace. Here's a screenshot of the search experience on Airbnb:

Airbnb Search Results

Let's imagine we have a room we'd like to rent on Airbnb. As hosts, if we try to charge above market price, renters will select more affordable alternatives and we won't make any money. On the other hand, if we set our nightly rent price too low, we'll miss out on potential revenue.

How can we hit the "sweet spot" in the middle? One strategy we could use is to:

- Find a few listings that are similar to ours,

- Average the listed price for the ones most similar to ours,

- And set our listing price to this calculated average price.

But doing that manually over and over again would be time-consuming, and we're data scientists! Instead of doing it manually, we're going to build a machine learning model to automate this process using a technique called k-nearest neighbors.

We'll start by taking a look at the data set we'll be working with.

Our Airbnb Data

Airbnb doesn't release any data on the listings in its marketplace, a but separate group named Inside Airbnb has extracted data on a sample of the listings for many of the major cities on the website. In this post, we'll be working with their data set from October 3, 2015 on the listings from Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. Here's a direct link to that data set.

Each row in the data set is a specific listing that's available for renting on Airbnb in the Washington, D.C. area. In machine learning terms, each row is an observation. The columns describe different characteristics of each listing (features, in machine learning terms).

To make the data set less cumbersome to work with, we've removed many of the columns in the original data set and renamed the file to dc_airbnb.csv.

Here are some of the more important columns (features) we'll want to work with, because these are all characteristics that a renter might use to assess which listing they will choose:

accommodates: the number of guests the rental can accommodatebedrooms: number of bedrooms included in the rentalbathrooms: number of bathrooms included in the rentalbeds: number of beds included in the rentalprice: nightly price for the rentalminimum_nights: minimum number of nights a guest can stay for the rentalmaximum_nights: maximum number of nights a guest can stay for the rentalnumber_of_reviews: number of reviews that previous guests have left

We'll start by reading our cleaned-up data set into pandas, printing its size and viewing the first few rows. (If you're not sure how to remove the superfluous columns from the original data set yourself, check out some of our pandas and data cleaning courses).

import pandas as pd

dc_listings = pd.read_csv('dc_airbnb.csv')

print(dc_listings.shape)

dc_listings.head()

(3723, 19)That looks good! Now, let's move on to the algorithm we'll be using for our machine learning model.

The K-nearest neighbors algorithm

The K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm works similarly to the three-step process we outlined earlier to compare our listing to similar listings and take the average price. Let's look at it in some more detail:

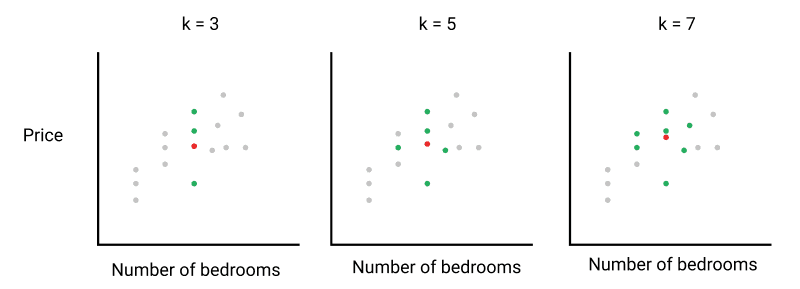

First, we select the number of similar listings k, that we want to compare with.

Second, we need to calculate how similar each listing is to ours using a similarity metric.

Third, we rank each listing using our similarity metric and select the first k listings.

Finally, we calculate the mean price for the k similar listings, and use that as our list price.

And while the images above use only two features (bedrooms and price) per observation to compare with our listing for the sake of simplicity, the beauty of machine learning is that we can do much more complex comparisons by assessing many more features for each observation.

Let's start building our real model by defining the similarity metric we're going to use. Then, we'll implement the k-nearest neighbors algorithm and use it to suggest a price for a new listing. For the purposes of this tutorial, we're going to use a fixed k value of 5, but once you become familiar with the workflow of the algorithm you can experiment with this value to see if you get better results with lower or higher k values.

Euclidean distance

When trying to predict a continuous value like price, the main similarity metric that's used is Euclidean distance. Here's the general formula for Euclidean distance: \(d = \sqrt{(q_1-p_1)^2 + (q_2-p_2)^2 + \cdots + (q_n-p_n)^2}\) where \( q_1 \) to \( q_n \) represent the feature values for one observation and \( p_1 \) to \( p_n \) represent the feature values for the other observation.

If your head just exploded, don't worry! We're going to break that down into smaller pieces. We'll start by...

Building a Basic KNN Model

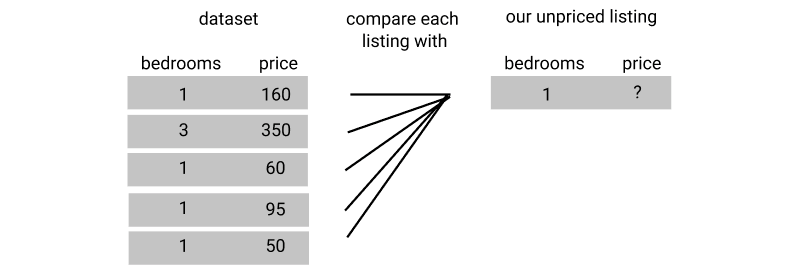

Let's start by breaking things down and looking at just one column from our data set. Here's the formula for just one feature: \(d = \sqrt{(q_1 - p_1)^2} \)

The square root and the squared power cancel and the formula simplifies to: \(d = | q_1 - p_1 | \)

Expressed in words, we want to find the absolute value of the difference between the observation and the data point we want to predict for the feature we're using.

For our purposes at the moment, let's say the living space that we want to rent can accommodate three people.

we'll first calculate the distance, using just the accommodates feature, between the first living space in the data set and our own. We can use the NumPy function np.abs() to get the absolute value.

import numpy as np

our_acc_value = 3

first_living_space_value = dc_listings.loc[0,'accommodates']

first_distance = np.abs(first_living_space_value - our_acc_value)

print(first_distance)

1The smallest possible Euclidian distance is zero, which would mean the observation we are comparing to is identical to ours, so the result we've gotten here makes sense. In isolation, however, the value doesn't mean much unless we know how it compares to other values. Let's calculate the Euclidean distance for each observation in our data set, and look at the range of values we have using pd.value_counts().

dc_listings['distance'] = np.abs(dc_listings.accommodates - our_acc_value)

dc_listings.distance.value_counts().sort_index()

0 461

1 2294

2 503

3 279

4 35

5 73

6 17

7 22

8 7

9 12

10 2

11 4

12 6

13 8

Name: distance, dtype: int64There are 461 listings that have a distance of 0, and thus accommodate the same number of people as our listing. Those listings might be a good place to start.

If we just used the first five values with a distance of 0, our predictions would be biased to the existing ordering of the data set. Instead, we'll randomize the ordering of the observations and then select the first five rows with a distance of 0. We're going to use DataFrame.sample() to randomize the rows. This method is usually used to select a random fraction of the DataFrame, but we'll tell it to randomly select 100

We'll also use the random_state parameter which just gives us a reproducible random order so anyone can follow along and get the exact same results.

dc_listings = dc_listings.sample(frac=1,random_state=0)

dc_listings = dc_listings.sort_values('distance')

dc_listings.price.head()

$75.002825

$120.002145

$90.002541

$50.003349

$105.00

Name: price, dtype: objectBefore we can take the average of our prices, you'll notice that our price column has the object type, due to the fact that the prices have dollar signs and commas (our sample above doesn't show the commas because all the values are less than $1000).

Let's clean this column by removing these characters and converting it to a float type, before calculating the mean of the first five values. We'll use pandas's Series.str.replace() to remove the stray characters and pass the regular expression \$|, which will match $ or ,.

dc_listings['price'] = dc_listings.price.str.replace("\$|,",'').astype(float)

mean_price = dc_listings.price.iloc[:5].mean()

mean_price88.0We've now made our first prediction --- our KNN model told us that when we're using just the accommodates feature find an appropriate price for our three-person listing, we should list our apartment for $88.00.

That's a good start! The problem is, we don't have any way to know how accurate this model is, which makes it impossible to optimize and improve. It's not a good idea to follow the predictions of any machine learning model without evaluating its accuracy!

Evaluating Our Model

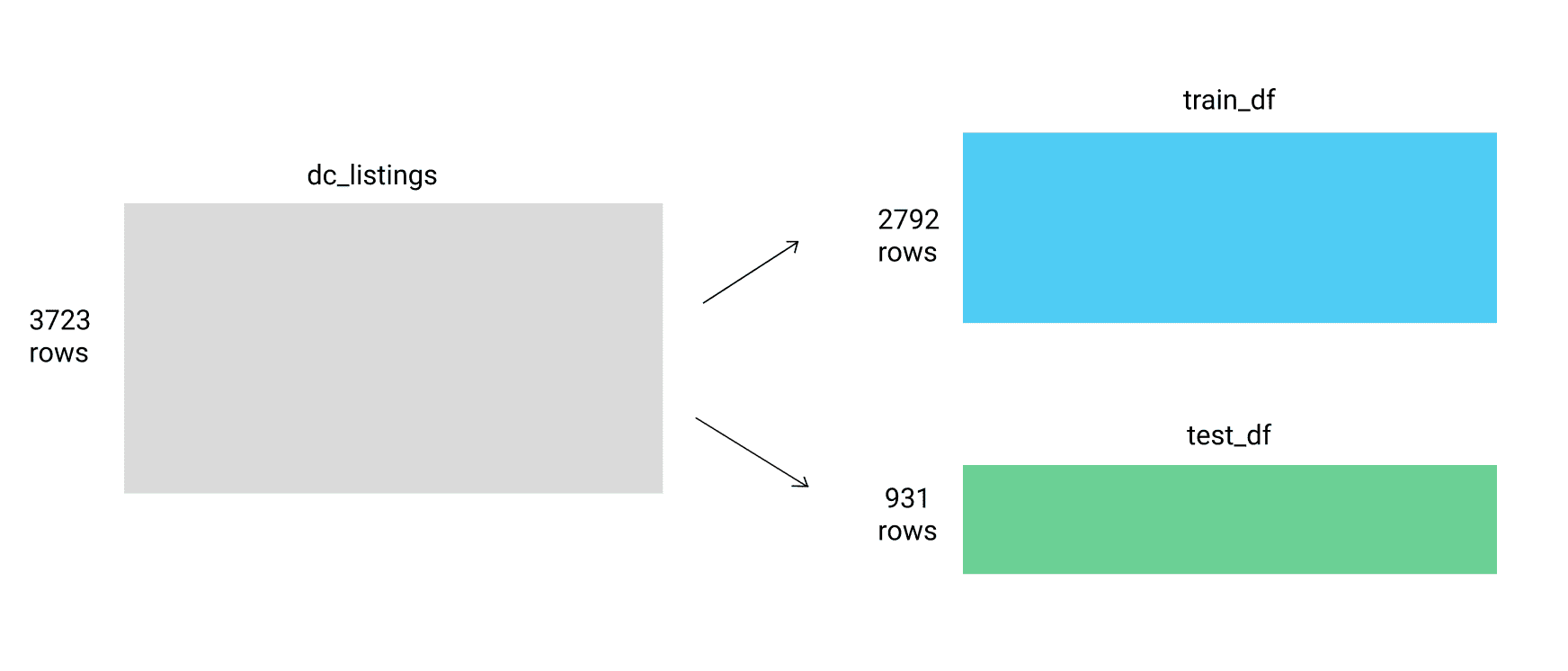

A simple way to test the quality of your model is to:

- Split the data set into 2 partitions:

- A training set: contains the majority of the rows (75

- A test set: contains the remaining minority of the rows (25

- Use the rows in the training set to predict the

pricevalue for the rows in the test set - Compare the predicted values with the actual

pricevalues in the test set to see how accurate the predicted values were.

We're going to follow this approach and split the 3,723 rows of our data set into two parts: train_df and test_df in a 75

Splitting into train and test dataframes

We'll also remove the column we added earlier when we created our first model.

dc_listings.drop('distance',axis=1)

train_df = dc_listings.copy().iloc[:2792]

test_df = dc_listings.copy().iloc[2792:]

To make things easier for ourselves while we look at metrics, we'll combine the model we made earlier into a function. We won't need to worry about randomizing the rows, since they're still randomized from earlier.

def predict_price(new_listing_value,feature_column):

temp_df = train_df

temp_df['distance'] = np.abs(dc_listings[feature_column] - new_listing_value)

temp_df = temp_df.sort_values('distance')

knn_5 = temp_df.price.iloc[:5]

predicted_price = knn_5.mean()

return(predicted_price)We can now use this function to predict values for our test dataset using the accommodates column.

test_df['predicted_price'] = test_df.accommodates.apply(predict_price,feature_column='accommodates')

Using RMSE to Evaluate Our Model

For many prediction tasks, we want to penalize predicted values that are further away from the actual value much more than those that are closer to the actual value.

To do this, we can take the mean of the squared error values, which is called the root mean squared error (RMSE). Here's the formula for RMSE: \( RMSE = \sqrt {\dfrac{ (actual_1-predicted_1)^2 + (actual_2-predicted_2)^2 + \cdots + (actual_n-predicted_n)^2 }{ n }}\) where n represents the number of rows in the test set. This formula might look overwhelming at first, but all we're doing is:

- Taking the difference between each predicted value and the actual value (or error),

- Squaring this difference (square),

- Taking the mean of all the squared differences (mean), and

- Taking the square root of that mean (root).

Hence, reading from bottom to top: root mean squared error. Let's calculate the RMSE value for the predictions we made on the test set.

test_df['squared_error'] = (test_df['predicted_price'] - test_df['price'])**(2)

mse = test_df['squared_error'].mean()

rmse = mse ** (1/2)

rmse212.98927967051529Our RMSE is about $213. One of the handy things about RMSE is that because we square and then take the square-root, the units for RMSE are the same as the value we are predicting, which makes it easy to understand the scale of our error.

In this case, that scale is pretty big — we're still fairly far from having an accurate prediction.

Comparing different models

With an error metric that we can use to see the accuracy of our model, let's create some predictions using different columns and look at how our error varies.

for feature in ['accommodates','bedrooms','bathrooms','number_of_reviews']:

test_df['predicted_price'] = test_df.accommodates.apply(predict_price,feature_column=feature)

test_df['squared_error'] = (test_df['predicted_price'] - test_df['price'])**(2)

mse = test_df['squared_error'].mean()

rmse = mse ** (1/2)

print("RMSE for the {} column: {}".format(feature,rmse))

RMSE for the accommodates column: 212.9892796705153

RMSE for the bedrooms column: 216.49048609414766

RMSE for the bathrooms column: 216.89419042215704

RMSE for the number_of_reviews column: 240.2152831433485We can see that the best model of the four that we trained is the one using the accomodates column.

However, the error rates we're getting are quite high relative to the range of prices of the listing in our data set. Predictions with these sorts of error rates would not be very helpful.

Thankfully, there's something we can do! So far, we've been training our model with only one feature, which is known as a univariate model. For more accuracy, we can have it assess multiple features at the same time, which is known as a multivariate model.

We're going to read in a cleaned version of this data set so that we can focus on evaluating the models. In our cleaned data set:

- All columns have been converted to numeric values, since we can't calculate the Euclidean distance of a value with non-numeric characters.

- Non numeric columns have been removed for simplicity.

- Any listings with missing values have been removed.

- We have normalized the columns which will give us more accurate results.

If you'd like to read more about data cleaning and preparing data for machine learning, you can read the excellent post Preparing and Cleaning Data for Machine Learning.

Let's read in this cleaned version, which is called dc_airbnb.normalized.csv, and preview the first few rows:

normalized_listings = pd.read_csv('dc_airbnb_normalized.csv')

print(normalized_listings.shape)

normalized_listings.head()(3671, 8)We'll then randomize the rows and split it into training and test data sets.

normalized_listings = normalized_listings.sample(frac=1,random_state=0)

norm_train_df = normalized_listings.copy().iloc[0:2792]

norm_test_df = normalized_listings.copy().iloc[2792:]Calculating Euclidean distance with multiple features

Let's remind ourselves what the original Euclidean distance equation looked like again: \(d = \sqrt{(q_1-p_1)^2 + (q_2-p_2)^2 + \cdots + (q_n-p_n)^2}\)

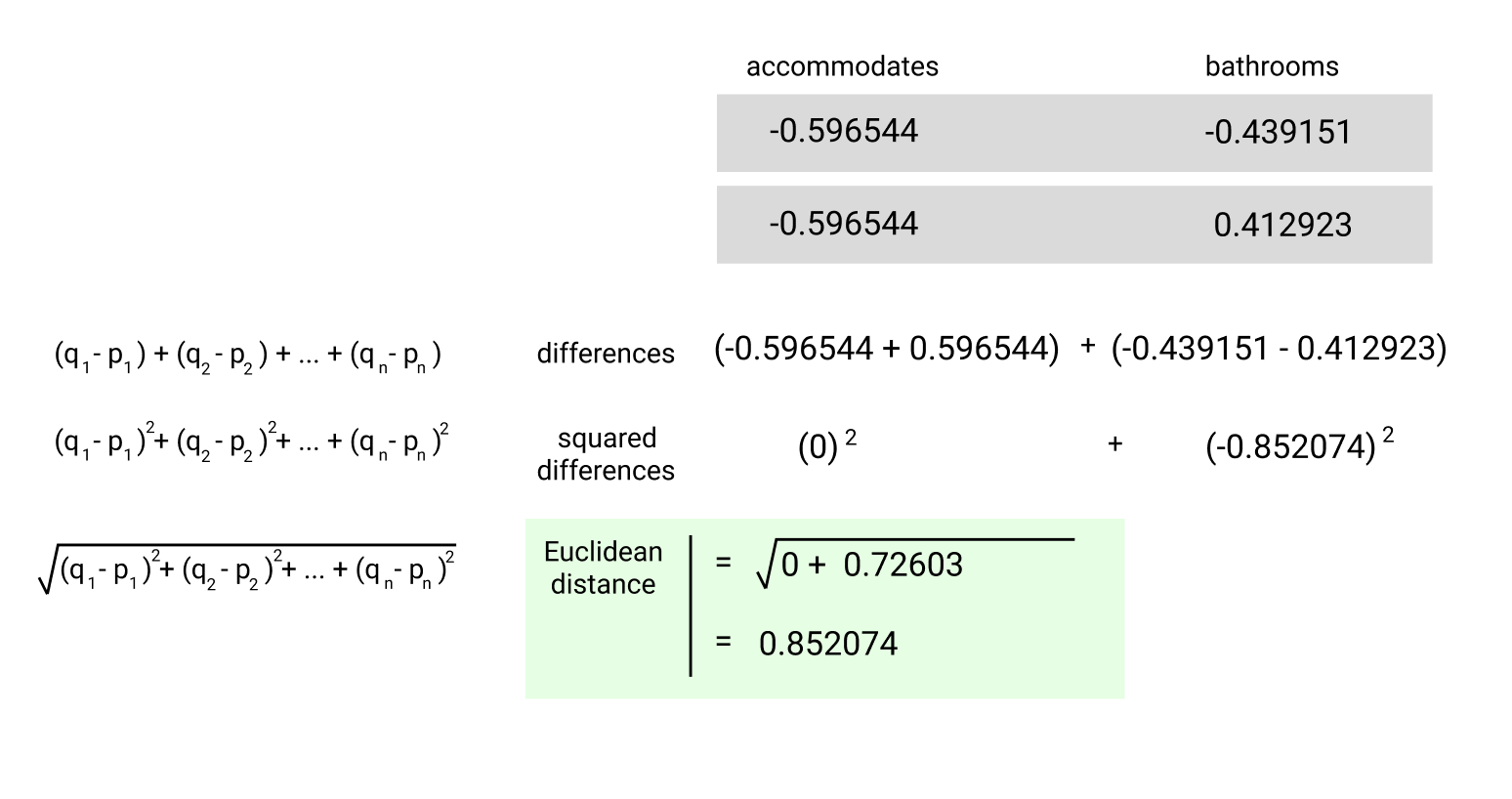

We're going to start by building a model that uses the accommodates and bathrooms features. For this case, our Euclidean equation would look like: \(d = \sqrt{(accommodates_1-accommodates_2)^2 + (bathrooms_1-bathrooms_2)^2 }\)

To find the distance between two living spaces, we need to calculate the squared difference between both accommodates values, the squared difference between both bathrooms values, add them together, and then take the square root of the resulting sum.

Here's what the Euclidean distance between the first two rows in normalized_listings looks like:

So far, we've been calculating Euclidean distance ourselves by writing the logic for the equation ourselves. We can instead use the distance.euclidean() function from scipy.spatial, which takes in two vectors as the parameters and calculates the Euclidean distance between them. The euclidean() function expects:

- both of the vectors to be represented using a list-like object (Python list, NumPy array, or pandas Series)

- both of the vectors must be one-dimensional and have the same number of elements

Let's use the euclidean() function to calculate the Euclidean distance between the first and fifth rows in our data set to practice.

from scipy.spatial import distance

first_listing = normalized_listings.iloc[0][['accommodates', 'bathrooms']]

fifth_listing = normalized_listings.iloc[20][['accommodates', 'bathrooms']]

first_fifth_distance = distance.euclidean(first_listing, fifth_listing)

first_fifth_distance0.9979095531766813Creating a multivariate KNN model

We can extend our previous function to use two features and our whole data set. Instead of distance.euclidean(), we're going to use distance.cdist(), because it allows us to pass multiple rows at once.

(The cdist() method can be used to calculate distance using a variety of methods, but it defaults to Euclidean.)

def predict_price_multivariate(new_listing_value,feature_columns):

temp_df = norm_train_df

temp_df['distance'] = distance.cdist(temp_df[feature_columns],[new_listing_value[feature_columns]])

temp_df = temp_df.sort_values('distance')

knn_5 = temp_df.price.iloc[:5]

predicted_price = knn_5.mean()

return(predicted_price)cols = ['accommodates', 'bathrooms']

norm_test_df['predicted_price'] = norm_test_df[cols].apply(predict_price_multivariate,feature_columns=cols,axis=1)

norm_test_df['squared_error'] = (norm_test_df['predicted_price'] - norm_test_df['price'])**(2)

mse = norm_test_df['squared_error'].mean()

rmse = mse ** (1/2)

print(rmse)122.702007943You can see that our RMSE improved from 212 to 122 when using two features instead of just accommodates. That's a huge improvement, although it's still not as accurate as we might like.

Introduction to scikit-learn

We've been writing functions from scratch to train our k-nearest neighbor models. This is helpful to understand how the mechanics work, but now that we understand the underlying fundamentals, we can work much more quickly and efficiently using Python's scikit-learn library.

Scikit-learn is the most popular machine learning library in Python. It has built-in functions for all of the major machine learning algorithms and a simple, unified workflow. Both of these properties allow data scientists to be incredibly productive when training and testing different models on a new data set.

The scikit-learn workflow consists of four main steps:

- Instantiate the specific machine learning model you want to use.

- Fit the model to the training data.

- Use the model to make predictions.

- Evaluate the accuracy of the predictions.

Each model in scikit-learn is implemented as a separate class and the first step is to identify the class we want to create an instance of.

Any model that helps us predict numerical values like the listing prices in our model is known as a regression model. The other main class of machine learning model is called classification. Classification models are used when we're trying to predict a label from a fixed set of labels (e.g. blood type or gender).

In our case, we want to use the KNeighborsRegressor class. The word regressor from the class name KNeighborsRegressor refers to the regression model class that we just discussed, and "KNeighbors" comes from the k-nearest neighbors model we're building.

Scikit-learn uses an object-oriented style similar to Matplotlib. We need to instantiate an empty model before doing anything else by calling the constructor.

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsRegressor

knn = KNeighborsRegressor()

If we refer to the documentation, we'll notice that by default:

n_neighbors: the number of neighbors, is set to5algorithm: for computing nearest neighbors, is set toautop: set to2, corresponding to Euclidean distance

Let's set the algorithm parameter to brute and leave the n_neighbors value as 5, which matches the manual implementation we built.

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsRegressor

knn = KNeighborsRegressor(algorithm='brute')

Fitting a Model and Making Predictions

Now, we can fit the model to the data using the fit method. For all models, the fit method takes in two required parameters:

- a matrix-like object, containing the feature columns we want to use from the training set.

- a list-like object, containing correct target values.

"Matrix-like object" means that the method is flexible and can accept either a pandas DataFrame or a NumPy 2D array. This means we can select the columns we want to use from the DataFrame and use that as the first parameter for the fit method.

For the second parameter, recall from earlier, all of the following are acceptable list-like objects:

- A NumPy array

- A Python list

- A pandas Series object (e.g. a column)

Let's select the target column from the DataFrame and use that as the second parameter to the fit method:

knn.fit(train_features, train_target)When the fit() method is called, scikit-learn stores the training data we specified within the KNearestNeighbors instance (knn). If we try passing in data containing missing values or non-numerical values into the fit method, scikit-learn will return an error. That's one of the wonderful things about this library — it contains many features like this to prevent us from making mistakes.

Now that we've specified the training data we want used to make predictions, we can use the predict method to make predictions about the test set. The predict method has only one required parameter:

- A matrix-like object, containing the feature columns from the data set we want to make predictions about

The number of feature columns we use during both training and testing need to match or scikit-learn will return an error.

predictions = knn.predict(test_features)The predict() method returns a NumPy array containing the predicted price values for the test set.

We now have everything you need to practice the entire scikit-learn workflow:

knn.fit(norm_train_df[cols], norm_train_df['price'])

two_features_predictions = knn.predict(norm_test_df[cols])

Of course, just because we're using scikit-learn instead of writing functions manually doesn't mean we can skip the evaluation step to see how accurate our model's predictions actually are!

Calculating MSE Using Scikit-Learn

Up until this point we have been calculating RMSE values manually, both using NumPy and SciPy functions to assist us. Alternatively, we can instead use the sklearn.metrics.mean_squared_error function().

The mean_squared_error() function takes in two inputs:

- A list-like object, representing the true values from your test set.

- A second list-like object, representing the predicted values generated by the model.

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

two_features_mse = mean_squared_error(norm_test_df['price'], two_features_predictions)

two_features_rmse = two_features_mse ** (1/2)

print(two_features_rmse)

124.834722314Not only is this much simpler from a syntax perspective, but it also takes less time for the model to run as scikit-learn has been heavily optimized for speed.

Notice that our RMSE is a little different from our manually implemented algorithm --- this is likely due to both differences in the randomization and slight differences in implementation between our 'manual' KNN algorithm and the scikit-learn version.

Be aware that changes to scikit-learn library itself can also affect these values somewhat. If you're following along with this tutorial and got a slightly different result, it's likely because you're using a newer version of scikit-learn.

Using More Features

One of the best things about scikit-learn is that it allows us to iterate more quickly. Let's give this a try by creating a model that uses four features instead of two and see if that improves our results.

knn = KNeighborsRegressor(algorithm='brute')

cols = ['accommodates','bedrooms','bathrooms','beds']

knn.fit(norm_train_df[cols], norm_train_df['price'])

four_features_predictions = knn.predict(norm_test_df[cols])

four_features_mse = mean_squared_error(norm_test_df['price'], four_features_predictions)

four_features_rmse = four_features_mse ** (1/2)

four_features_rmse120.92729413345498In this case, our error went down slightly. It may not always do that as you add features, though. This is an important thing to be aware of: adding more features does not necessarily produce a more accurate model.

This is because adding a feature that is not an accurate predictor of your target variable adds 'noise' to your model.

Summary

Let's take a look at what we've learned:

- We learned what machine learning is, and walked through a very basic, manual 'model' for predicting a house's sale price.

- We learned about the k-nearest neighbors algorithm, built a univariate model (only one feature) from scratch in Python, and used it to make predictions.

- We learned that RMSE can be used to calculate the error of our models, which we can then use to iterate and try and improve our predictions.

- We then created a multivariate (more than one feature) model from scratch and used that to make better predictions.

- Finally, we learned about the scikit-learn library, and used the

KNeighborsRegressorclass to make predictions.

Next Steps

If you'd like to learn more, this tutorial is based on our Dataquest Machine Learning Fundamentals course, which is part of our Data Science Learning Path. The course goes into a lot more detail and improves on the model built in this post, while allowing you to follow along, writing code in your browser that's checked at each step by our answer-checking system to ensure you're doing everything correctly.

If you'd like to continue working on this model on your own, here are a few things you can to do improve accuracy:

- Try substituting in different values for

k. - Go back to the original data set and convert some of the columns we removed to numeric (our Preparing and Cleaning Data for Machine Learning post will help you here) and experiment with adding different combinations of features.

- Try some feature engineering, where you create new columns based on existing data: Our Getting Started with Kaggle: House Prices Competition article has a simple of example of this.

This post was updated in July 2019.