Working with SQLite Databases using Python and Pandas

SQLite is a database engine that makes it simple to store and work with relational data. Much like the csv format, SQLite stores data in a single file that can be easily shared with others. Most programming languages and environments have good support for working with SQLite databases. Python is no exception, and a library to access SQLite databases, called sqlite3, has been included with Python since version 2.5.

In this post, we’ll walk through how to use sqlite3 to create, query, and update databases. We’ll also cover how to simplify working with SQLite databases using the pandas package. We’ll be using Python 3.5, but this same approach should work with Python 2.

If you want to learn the basics of SQL, you might like to checkout our SQL basics blogpost first.

Before we get started, let’s take a quick look at the data we’ll be working with. We’ll be looking at airline flight data, which contains information on airlines, airports, and routes between airports. Each route represents a repeated flight that an airline flies between a source and a destination airport.

All of the data is in a SQLite database called flights.db, which contains three tables — airports, airlines, and routes. You can download the data here.

Here are two rows from the airlines table:

| id | name | alias | iata | icao | callsign | country | active | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 11 | 4D Air | \N | NaN | QRT | QUARTET | Thailand | N |

| 11 | 12 | 611897 Alberta Limited | \N | NaN | THD | DONUT | Canada | N |

As you can see above, each row is a different airline, and each column is a property of that airline, such as name, and country. Each airline also has a unique id, so we can easily look it up when we need to.

Here are two rows from the airports table:

| id | name | city | country | code | icao | latitude | longitude | altitude | offset | dst | timezone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | Goroka | Goroka | Papua New Guinea | GKA | AYGA | -6.081689 | 145.391881 | 5282 | 10 | U | Pacific/Port_Moresby |

| 1 | 2 | Madang | Madang | Papua New Guinea | MAG | AYMD | -5.207083 | 145.7887 | 20 | 10 | U | Pacific/Port_Moresby |

As you can see, each row corresponds to an airport, and contains information on the location of the airport. Each airport also has a unique id, so we can easily look it up.

Here are two rows from the routes table:

| airline | airline_id | source | source_id | dest | dest_id | codeshare | stops | equipment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2B | 410 | AER | 2965 | KZN | 2990 | NaN | 0 | CR2 |

| 1 | 2B | 410 | ASF | 2966 | KZN | 2990 | NaN | 0 | CR2 |

Each route contains an airline_id, which the id of the airline that flies the route, as well as source_id, which is the id of the airport that the route originates from, and dest_id, which is the id of the destination airport for the flight.

Now that we know what kind of data we’re working with, let’s start by connecting to the database and running a query.

Querying database rows in Python

In order to work with a SQLite database from Python, we first have to connect to it. We can do that using the connect function, which returns a Connection object:

import sqlite3

conn = sqlite3.connect("flights.db")Once we have a Connection object, we can then create a Cursor object. Cursors allow us to execute SQL queries against a database:

cur = conn.cursor()Once we have a Cursor object, we can use it to execute a query against the database with the aptly named execute method. The below code will fetch the first 5 rows from the airlines table:

cur.execute("select * from airlines limit 5;")You may have noticed that we didn’t assign the result of the above query to a variable. This is because we need to run another command to actually fetch the results. We can use the fetchall method to fetch all of the results of a query:

results = cur.fetchall()

print(results)[(0, '1', 'Private flight', '\\N', '-', None, None, None, 'Y'), (1, '2', '135 Airways', '\\N', None, 'GNL', 'GENERAL', 'United States', 'N'), (2, '3', '1Time Airline', '\\N', '1T', 'RNX', 'NEXTIME', 'South Africa', 'Y'), (3, '4', '2 Sqn No 1 Elementary Flying Training School', '\\N', None, 'WYT', None, 'United Kingdom', 'N'), (4, '5', '213 Flight Unit', '\\N', None, 'TFU', None, 'Russia', 'N')]As you can see, the results are formatted as a list of tuples. Each tuple corresponds to a row in the database that we accessed. Dealing with data this way is fairly painful. We’d need to manually add column heads, and manually parse the data. Luckily, the pandas library has an easier way, which we’ll look at in the next section.

Before we move on, it’s good practice to close Connection objects and Cursor objects that are open. This prevents the SQLite database from being locked. When a SQLite database is locked, you may be unable to update the database, and may get errors. We can close the Cursor and the Connection like this:

cur.close()

conn.close()Mapping airports

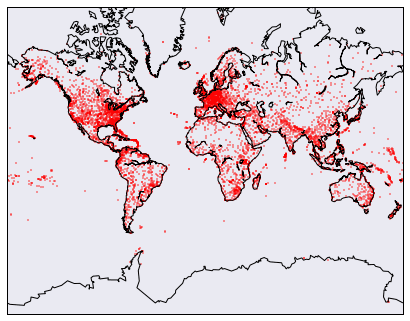

Using our newfound knowledge of queries, we can create a plot that shows where all the airports in the world are. First, we query latitudes and longitudes:

import sqlite3

conn = sqlite3.connect("flights.db")

cur = conn.cursor()

coords = cur.execute("""

select cast(longitude as float),

cast(latitude as float)

from airports;""").fetchall()The above query will retrieve the latitude and longitude columns from airports, and convert both of them to floats. We then call the fetchall method to retrieve them.

We then need to setup our plotting by importing matplotlib, the primary plotting library for Python. Combined with the basemap package, this allows us to create maps only using Python.

We first need to import the libraries:

from mpl_toolkits.basemap import Basemap

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltThen, we setup our map, and draw the continents and coastlines that will form the background of our map:

m = Basemap(

projection='merc',

llcrnrlat=-80,

urcrnrlat=80,

llcrnrlon=-180,

urcrnrlon=180,

lat_ts=20,

resolution='c')

m.drawcoastlines()

m.drawmapboundary()Finally, we plot the coordinates of each airport onto the map. We retrieved a list of tuples from the SQLite database. The first element in each tuple is the longitude of the airport, and the second is the latitude. We’ll convert the longitudes and latitudes into their own lists, and then plot them on the map:

x, y = m(

[l[0] for l in coords],

[l[1] for l in coords])

m.scatter(

x,

y,

1, marker='o',

color='red')We end up with a map that shows every airport in the world:

As you may have noticed, working with data from the database is a bit painful. We needed to remember which position in each tuple corresponded to what database column, and manually parse out individual lists for each column. Luckily, the pandas library gives us an easier way to work with the results of SQL queries.

Reading results into a pandas DataFrame

We can use the pandas read_sql_query function to read the results of a SQL query directly into a pandas DataFrame. The below code will execute the same query that we just did, but it will return a DataFrame. It has several advantages over the query we did above:

- It doesn’t require us to create a Cursor object or call

fetchallat the end. - It automatically reads in the names of the headers from the table.

- It creates a DataFrame, so we can quickly explore the data.

import pandas as pd

import sqlite3

conn = sqlite3.connect("flights.db")

df = pd.read_sql_query("select * from airlines limit 5;", conn)

df| index | id | name | alias | iata | icao | callsign | country | active | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | Private flight | \N | – | None | None | None | Y |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 135 Airways | \N | None | GNL | GENERAL | United States | N |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 1Time Airline | \N | 1T | RNX | NEXTIME | South Africa | Y |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 Sqn No 1 Elementary Flying Training School | \N | None | WYT | None | United Kingdom | N |

| 4 | 4 | 5 | 213 Flight Unit | \N | None | TFU | None | Russia | N |

As you can see, we get a nicely formatted DataFrame as the result. We could easily manipulate the columns:

df["country"]0 None

1 United States

2 South Africa

3 United Kingdom

4 Russia

Name: country, dtype: objectIt’s highly recommended to use the read_sql_query function when possible.

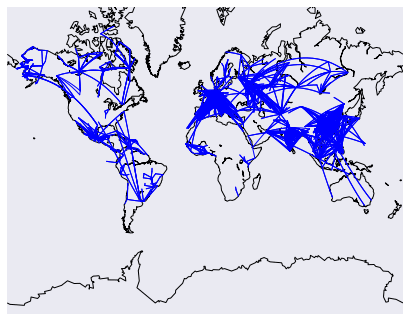

Mapping routes

Now that we know how to read queries into pandas DataFrames, we can create a map of every airline route in the world. We first start by querying the data. The below query will:

- Get the latitude and longitude for the source airport for each route.

- Get the latitude and longitude for the destination airport for each route.

- Convert all the coordinate values to floats.

- Read the results into a DataFrame, and store them to the variable

routes.

routes = pd.read_sql_query("""

select cast(sa.longitude as float) as source_lon,

cast(sa.latitude as float) as source_lat,

cast(da.longitude as float) as dest_lon,

cast(da.latitude as float) as dest_lat

from routes

inner join airports sa on sa.id = routes.source_id

inner join airports da on da.id = routes.dest_id;

""",

conn)We then setup our map:

m = Basemap(

projection='merc',

llcrnrlat=-80,

urcrnrlat=80,

llcrnrlon=-180,

urcrnrlon=180,

lat_ts=20,

resolution='c'

)

m.drawcoastlines()We iterate through the first 3000 rows, and draw them. The below code will:

- Loop through the first

3000rows inroutes. - Figure out if the route is too long.

- If the route isn’t too long:

- Draw a circle between the origin and the destination.

for name, row in routes[:3000].iterrows():

if abs(row["source_lon"] - row["dest_lon"]) < 90:

# Draw a great circle between source and dest airports.

m.drawgreatcircle(

row["source_lon"],

row["source_lat"],

row["dest_lon"],

row["dest_lat"],

linewidth=1,

color='b'

)We end up with the following map:

The above is much more efficient when we use pandas to turn the results of the SQL query into a DataFrame, instead of working with the raw results from sqlite3.

Now that we know how to query database rows, let’s move on to modifying them.

Modifying database rows

We can use the sqlite3 package to modify a SQLite database by inserting, updating, or deleting rows. Creating the Connection is the same for this as it is when you’re querying a table, so we’ll skip that part.

Inserting rows with Python

To insert a row, we need to write an INSERT query. The below code will add a new row to the airlines table. We specify 9 values to insert, one for each column in airlines. This will add a new row to the table.

cur = conn.cursor()

cur.execute("insert into airlines values (6048, 19846, 'Test flight', '', '', null, null, null, 'Y')")If you try to query the table now, you actually won’t see the new row yet. Instead you’ll see that a file was created called flights.db-journal. flights.db-journal is storing the new row until you’re ready to commit it to the main database, flights.db.

SQLite doesn’t write to the database until you commit a transaction. A transaction consists of 1 or more queries that all make changes to the database at once. This is designed to make it easier to recover from accidental changes, or errors. Transactions allow you to run several queries, then finally alter the database with the results of all of them. This ensures that if one of the queries fails, the database isn’t partially updated.

A good example is if you have two tables, one of which contains charges made to people’s bank accounts (charges), and another which contains the dollar amount in the bank accounts (balances). Let’s say a bank customer, Roberto, wants to send $50 to his sister, Luisa. In order to make this work, the bank would need to:

- Create a row in

chargesthat says $50 is being taken from Roberto’s account and sent to Luisa. - Update Roberto’s row in the

balancestable and remove $50. - Update Luisa’s row in the

balancestable and add $50.

These will require three separate SQL queries to update all of the tables. If a query fails, we’ll be stuck with bad data in our database. For example, if the first two queries work, then the third fails, Roberto will lose his money, but Luisa won’t get it. Transactions mean that the main database isn’t updated unless all the queries succeed. This prevents the system from getting into a bad state, where customers lose their money.

By default, sqlite3 opens a transaction when you do any query that modifies the database. You can read more about it here. We can commit the transaction, and add our new row to the airlines table, using the commit method:

conn.commit()Now, when we query flights.db, we’ll see the extra row that contains our test flight:

pd.read_sql_query("select * from airlines where id=19846;", conn)| index | id | name | alias | iata | icao | callsign | country | active | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 19846 | Test flight | None | None | None | Y |

Passing parameters into a query

In the last query, we hardcoded the values we wanted to insert into the database. Most of the time, when you insert data into a database, it won’t be hardcoded, it will be dynamic values you want to pass in. These dynamic values might come from downloaded data, or might come from user input.

When working with dynamic data, it might be tempting to insert values using Python string formatting:

cur = conn.cursor()

name = "Test Flight"

cur.execute("insert into airlines values (6049, 19847, {0}, '', '', null, null, null, 'Y')".format(name))

conn.commit()You want to avoid doing this! Inserting values with Python string formatting makes your program vulnerable to SQL Injection attacks. Luckily, sqlite3 has a straightforward way to inject dynamic values without relying on string formatting:

cur = conn.cursor()

values = ('Test Flight', 'Y')

cur.execute("insert into airlines values (6049, 19847, ?, '', '', null, null, null, ?)", values)

conn.commit()Any ? value in the query will be replaced by a value in values. The first ? will be replaced by the first item in values, the second by the second, and so on. This works for any type of query. This created a SQLite parameterized query, which avoids SQL injection issues.

Updating rows

We can modify rows in a SQLite table using the execute method:

cur = conn.cursor()

values = ('USA', 19847)

cur.execute("update airlines set country=? where id=?", values)

conn.commit()We can then verify that the update happened:

pd.read_sql_query("select * from airlines where id=19847;", conn)| index | id | name | alias | iata | icao | callsign | country | active | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6049 | 19847 | Test Flight | None | None | USA | Y |

Deleting rows

Finally, we can delete the rows in a database using the execute method:

cur = conn.cursor()values = (19847, )

cur.execute("delete from airlines where id=?", values)conn.commit()We can then verify that the deletion happened, by making sure no rows match our query:

pd.read_sql_query("select * from airlines where id=19847;", conn)| index | id | name | alias | iata | icao | callsign | country | active |

|---|

Creating tables

We can create tables by executing a SQL query. We can create a table to represent each daily flight on a route, with the following columns:

id— integerdeparture— date, when the flight left the airportarrival— date, when the flight arrived at the destinationnumber— text, the flight numberroute_id— integer, the id of the route the flight was flying

cur = conn.cursor()

cur.execute("create table daily_flights (id integer, departure date, arrival date, number text, route_id integer)")conn.commit()Once we create a table, we can insert data into it normally:

cur.execute("insert into daily_flights values (1, '2016-09-28 0:00', '2016-09-28 12:00', 'T1', 1)")

conn.commit()When we query the table, we’ll now see the row:

pd.read_sql_query("select * from daily_flights;", conn)| id | departure | arrival | number | route_id | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2016-09-28 0:00 | 2016-09-28 12:00 | T1 | 1 |

Creating tables with pandas

The pandas package gives us a much faster way to create tables. We just have to create a DataFrame first, then export it to a SQL table. First, we’ll create a DataFrame:

from datetime import datetime

df = pd.DataFrame(

[[1, datetime(2016, 9, 29, 0, 0) ,

datetime(2016, 9, 29, 12, 0), 'T1', 1]],

columns=["id", "departure", "arrival", "number", "route_id"])Then, we’ll be able to call the to_sql method to convert df to a table in a database. We set the keep_exists parameter to replace to delete and replace any existing tables named daily_flights:

df.to_sql("daily_flights", conn, if_exists="replace")We can then verify that everything worked by querying the database:

pd.read_sql_query("select * from daily_flights;", conn)| index | id | departure | arrival | number | route_id | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 2016-09-29 00:00:00 | 2016-09-29 12:00:00 | T1 | 1 |

Altering tables with Pandas

One of the hardest parts of working with real-world data science is that the data you have per record changes often. Using our airline example, we may decide to add an airplanes field to the airlines table that indicates how many airplanes each airline owns. Luckily, there’s a way to alter a table to add columns in SQLite:

cur.execute("alter table airlines add column airplanes integer;")Note that we don’t need to call commit — alter table queries are immediately executed, and aren’t placed into a transaction. We can now query and see the extra column:

pd.read_sql_query("select * from airlines limit 1;", conn)| index | id | name | alias | iata | icao | callsign | country | active | airplanes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | Private flight | \N | – | None | None | None | Y | None |

Note that all the columns are set to null in SQLite (which translates to None in Python) because there aren’t any values for the column yet.

Altering tables with Pandas

It’s also possible to use Pandas to alter tables by exporting the table to a DataFrame, making modifications to the DataFrame, then exporting the DataFrame to a table:

df = pd.read_sql("select * from daily_flights", conn)

df["delay_minutes"] = None

df.to_sql("daily_flights", conn, if_exists="replace")The above code will add a column called delay_minutes to the daily_flights table.

Next Steps

You should now have a good grasp on how to work with data in a SQLite database using Python and pandas. We covered querying databases, updating rows, inserting rows, deleting rows, creating tables, and altering tables. This covers all of the major SQL operations, and almost everything you’d work with on a day to day basis.

If you’re interested in learning more about how to work with Python and SQL, you can check out our interactive SQL course at Dataquest.

Here are some supplemental resources if you want to dive deeper:

Lastly, if you want to keep practicing, you can download the file we used in this blog post, flights.db, here.